Mapping the maze: a system-wide analysis of commercial real estate exposures and risks

Published as part of the Macroprudential Bulletin 25, November 2024

This article analyses the complex linkages between commercial real estate (CRE) markets and the financial system. Examining data from a wide range of sources this article presents the first system-wide mapping of CRE exposures in the euro area. The exercise identifies several sectors – real estate companies, real estate investment funds and real estate investment trusts – with particularly large CRE exposures. Structural vulnerabilities among these key players increase their exposure to CRE market shocks and the likelihood that they could amplify these shocks. In the case of real estate investment funds, highlighting the need to develop a comprehensive macroprudential framework to address liquidity vulnerabilities. Moreover, the complexity of CRE exposures that arise from extensive debt and equity linkages between these key owners of CRE and their financiers adds a further layer of risk, with the potential to exacerbate uncertainty and feedback loops. Findings underline the importance of closely monitoring links between CRE and the financial system and continuing work to close data gaps related to these markets.

1 Introduction

Commercial real estate markets (CRE) are in a clear downturn, but data gaps still pose challenges to our understanding of how this could affect financial stability. CRE markets face both cyclical and structural challenges arising from higher financing costs, the shift towards remote working and increased costs from sustainability-related renovation requirements (see Ryan et al., 2023). Past experience shows that fluctuations in CRE markets can have serious implications for financial stability (see Lang et al., 2022, and Ryan et al., 2022). However, persistent data gaps continue to pose challenges to our understanding of who is exposed to euro area CRE and hence of how a large CRE shock could transmit through the financial system.

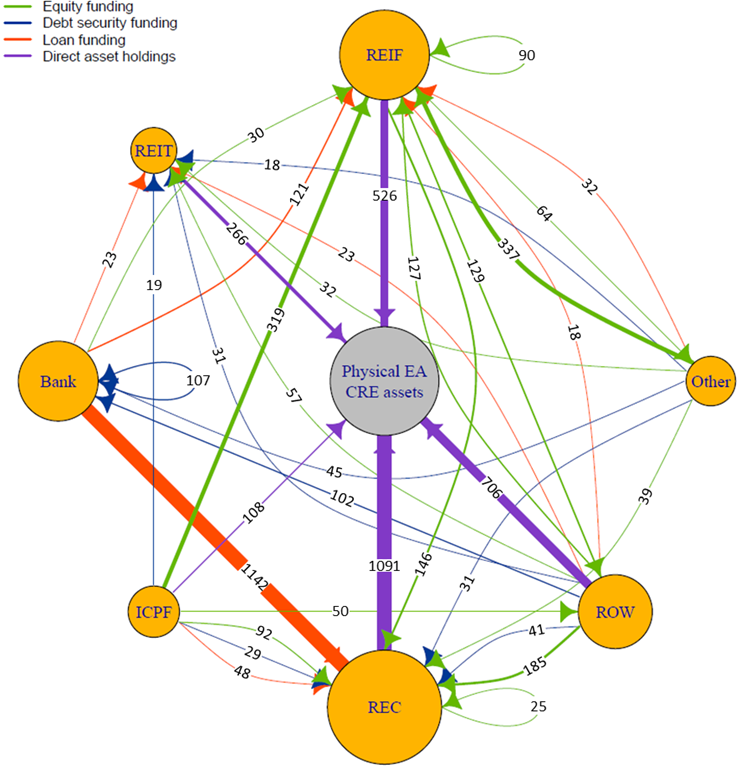

Despite this, a system-wide mapping of euro area CRE exposures and interconnectedness across sectors has not been undertaken to date. Analysis of CRE-related risks has typically focused on individual sectors, particularly banks or real estate investment funds (REIFs) (see, for example, Ryan et al., 2022, and Daly et al., 2023). This research provides crucial insights into the vulnerabilities and risks facing these sectors. However, the absence of a system-wide mapping of euro area CRE exposures to date means our understanding of the size of these exposures, and the interconnectedness across CRE investor sectors, remains limited. This article aims to provide new insight into who is exposed to euro area CRE − via both direct ownership and the financing of ownership − and the complex network of linkages across sectors that arise from these exposures (Chart 1). In doing so, it provides a clearer understanding of the potential impact a CRE downturn may have on the wider financial system.[2] This includes how interconnections between sectors could lead to potential feedback loops and contribute to systemic risk. It should be noted that estimates provided in this piece are calculated on a best-effort basis as available data remains imperfect. For example, complex structures of firms and funds make it difficult to ensure that loans and securities associated with all subsidiaries are captured. Analysis focuses primarily on income generating CRE as measures of the total stock of own-use CRE in the euro area are not available.

Financial and real economy players can be exposed to a CRE downturn via ownership or financing of CRE, with different financial stability transmission mechanisms relevant in each case. Owners of CRE assets are directly exposed to losses arising from falling CRE prices and/or rents. Such losses, where severe enough, could result in firms facing the risk of default or triggering investor outflows for entities like REIFs. In turn, such outcomes would have implications for a second type of CRE market player – the financial actors who fund such businesses. Banks and bond investors are exposed to CRE via a debt financing channel, where a severe CRE market downturn would increase the likelihood of default on their exposures. Where CRE is also used as collateral for exposures, loss given default would also increase. A third set of market players are exposed via equity financing: those who own shares issued by real estate companies (RECs), real estate investment funds (REIFs) and real estate investment trusts (REITs). A market correction also exposes these players to reduced profitability or losses on their exposures.

2 Who owns physical commercial real estate assets in the euro area?

Euro area RECs, REIFs and REITs are major investors in the euro area CRE market, directly exposing them to its current downturn. We estimate that the total value of the physical euro area CRE market at the end of 2023 amounted to €2.7 trillion.[3] RECs appear to own the largest share of this market (at least €1.1 trillion), followed by REIFs (€526 billion), REITs (€266 billion) and insurance corporations and pension funds (ICPFs) (€108 billion) (Chart 1). Subtracting these sectors’ holdings from the total indicates that residual ownership by other euro area and non-euro area investors amount to €706 billion, or 26% of the physical market. Non-euro area investors likely comprise the majority of this segment. As Ryan et al. (2022) show, non-euro area investors have accounted for a third of annual purchases in euro area CRE markets over the past two decades. Allowing for sales by this sector, this roughly aligns with our 26% figure. The rest of this article will focus on euro area players only, due to their greater relevance for euro area financial stability.

Chart 1

Network of cross-sectoral CRE exposures and interconnectedness by instrument

(nodes: size of sectoral CRE exposures (EUR billions); edges: size of links by instrument type (EUR billions))

Sources: ECB (IVF, SHSS, AnaCredit), EIOPA, Moody’s Analytics, S&P Capital IQ, Bloomberg Finance L.P., RCA, C&W and MSCI.

Notes: The date of observation is Q4 2023. Exposures below €18 billion are not shown in the chart. “Other” denotes other euro area investors (i.e. governments, households, non-real estate investment funds and other financial intermediaries). The direction of arrows for loans, debt securities and equities indicates funding flows, e.g. an equity arrow of €146 billion going from REIF to REC suggests that REIFs fund RECs by holding €146 billion of REC equity, while an arrow of €526 billion from REIF to physical EA CRE assets indicates that REIFs hold €526 billion of the physical euro area CRE market. The nodes cover euro area-domiciled counterparties, except ROW, which encompasses all non-euro area sectors. Sector breakdowns of covered CRE bonds have been estimated by splitting Moody’s data on total issued CRE covered bonds, based on SHSS data on a selection of covered bonds issued by large CRE bond issuers. Equity, debt security and loan financing have been estimated using ECB statistical datasets (IVF, SHSS, AnaCredit) and EIOPA statistics for ICPFs, complemented by commercial sources to identify public and private counterparties. Private company data have been gathered using a combination of commercial and ECB statistical data to overcome data availability challenges. Subsidiaries of firms have been included in loan data and security issuance data. REITs have been identified using a combination of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and S&P Capital IQ data and part of residual loans from ROW to REITs has been estimated using REITs’ balance sheet data, together with ECB statistical data sources (AnaCredit and SHSS). Note that ROW holdings of Physical EA CRE assets also include holdings by some non-categorised EA entities.

REIFs are subject to liquidity mismatches which make them vulnerable to a CRE downturn and could also amplify the downturn. In the past decade the REIF sector has tripled in size (Chart 2, panel a). Consequently, it is becoming an increasingly important channel of investment for the euro area CRE market, with its significance varying across countries (see Daly et al., 2023). However, as most REIFs’ portfolios consist of CRE assets, falling property values or rental incomes negatively impact their returns. For open-ended REIFs, which can face a structural mismatch between their asset liquidity and redemption terms, declining returns increase the likelihood of rising investor redemptions.[4] This raises the potential for forced asset sales by funds to fulfil redemption requests, especially in countries with low cash buffers (Chart 2, panel b).[5] Such outflows could be triggered by growing internalisation of unrealised losses on CRE exposures, for instance (see ECB, 2024). Additionally, some funds may face leverage vulnerabilities, with refinancing or debt servicing pressures stemming from higher interest rates. In turn, this means that leverage could also increase the risk of forced deleveraging (see Special Focus A in this edition of the Macroprudential Bulletin). Given the growing footprint of REIFs in CRE markets, forced sales would likely further compound declines in CRE prices and liquidity, which would have a negative impact on the value of assets and collateral owned by other sectors.

Chart 2

Growth and liquidity vulnerabilities of euro area REIFs

a) Growth of euro area REIFs | b) Open-ended share and cash buffers |

|---|---|

(net asset value, EUR billions) | (percentage shares of net asset value) |

|  |

Sources: ECB (IVF) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: NAV stands for net asset value. Panel b: The Cash/NAV ratio reflects the value of cash holdings as a percentage of NAV. The date of observation is Q4 2023.

Moreover, analysis of a sample of large REIFs suggest stress in the sector could also have cross-border implications. Data compiled from financial statements for large REIFs with €213 billion in CRE assets – almost 20% of the sector’s total – highlight extensive cross-border exposures (Chart 3, panel a).[6] While many of these large funds invest heavily in CRE located in their home country, those domiciled in Germany and Luxembourg appear to have significant investments in other euro area countries. This implies that stress in these funds could also impact CRE markets in other countries. Additionally, large French and German REIFs have substantial holdings of office properties (Chart 3, panel b), exposing them to losses arising from falling demand for office space as firms shift towards hybrid working arrangements. In the absence of detailed fund-level and portfolio-level data, however, it is not currently possible to assess the extent of the risks facing these funds, or the broader REIF sector.

Chart 3

Some large REIFs have extensive cross-border exposures

a) CRE assets by property location | b) CRE assets by property type |

|---|---|

(EUR billions) | (EUR billions) |

|  |

Sources: Company financial statements and ECB calculations.

Notes: Based on a sample of 37 large REIFs for which data on property holdings by country and sector could be identified. The funds’ domicile is presented on the x-axis. “Other EA” reflects a small number of large REIFs domiciled in other euro area countries.

REITs and RECs also have large exposures to physical CRE, but their vulnerabilities stem mainly from high leverage. These investors are typically institutional landlords or property development firms, which is reflected in the fact that over 70% of their total assets are physical CRE holdings. While euro area REITs are publicly listed entities, RECs can be either publicly listed or privately held (unlisted). Bloomberg data show that REITs hold a total of €266 billion in CRE assets. Separately, data from Capital IQ for RECs – including publicly-listed and private real estate companies - in the euro area indicates they hold a further €1.1 trillion in CRE assets.[7] [8] Falling prices and rents on these assets expose firms to losses. Their capacity to absorb these losses may be further undermined by rising financing costs. Most at risk are highly leveraged firms and firms reliant on short-term/variable-rate financing (see Ryan et al., 2023). As with REIFs difficulties in servicing or refinancing debt could result in forced deleveraging and asset sales by companies. Furthermore, given their market footprint, stress in this sector would have significant consequences for underlying CRE markets, as well as the financiers of these firms. This effect may be amplified where companies use CRE as collateral, with falling CRE prices also reducing their access to credit via the collateral channel (see Horan et al., 2023).

By contrast, insurance companies and pension funds (ICPFs) do not appear to be significantly exposed to CRE via direct ownership, which accounts for only 1% of their total assets. Consequently, losses on direct exposures would not pose significant concerns for the stability of the sector as a whole. In addition, ICPFs do not use financial leverage to fund their CRE investments or face structural liquidity mismatches. Rather, the main CRE-related risk facing ICPFs is the potential for larger losses stemming from indirect exposures to CRE, which bring their total exposure to CRE markets to 7% of total assets. These debt and equity exposures are discussed in more detail below.

3 Lending to euro area commercial real estate investors

Euro area banks have approximately €1.3 trillion in outstanding loans to CRE investors, making them a crucial source of financing for CRE markets. The ECB’s AnaCredit dataset provides loan-level data on loans made by euro area banks to euro area firms and other financial actors.[9] At the end of 2023, this dataset captured €1.1 trillion in loans to euro area RECs, €23 billion in loans to REITs and €121 billion in loans to REIFs (Chart 1).[10] Special Focus A documents for the first time the links between REIFs and banks. Comparing the size of funding links examined in this article shows that bank loans appear to be the dominant source of debt financing, and hence leverage, among euro area RECs and REIFs, while REITs make extensive use of bond financing (Chart 1).

These bank loans are highly exposed to potential losses arising from the current market downturn. Microsimulation analysis carried out by Ryan et al. (2023) identifies significant vulnerabilities in this loan book arising from rising financing costs and falling firm profits. Credit quality is already visibly deteriorating, with the NPL ratio doubling since the start of the most recent monetary tightening cycle (see ECB, 2024). In addition to increasing the probability of default on these exposures, the market downturn increases loss given default on exposures collateralised by CRE. AnaCredit data show that around a third of banks’ NFC lending is collateralised by some form of CRE (Chart 4, panel a).[11]

However, this loan portfolio accounts for only 6% of total euro area bank assets and is unlikely to threaten the solvency of the banking system. Large losses in the banking system can impair the sector’s capacity to carry out its financial intermediation function, with severe implications for the wider economy. Although bank lending is the primary source of finance for much of the euro area CRE market, the limited size of this loan portfolio relative to banks’ total balance sheets and banks’ healthy capital positions mean that the CRE loan book is unlikely to cause this form of stress (see ECB, 2024). However, exposures are not evenly spread across banks, and a tail of smaller, specialised banks with larger exposures (>10% total assets), accounting for approximately 13% of euro area bank assets, may experience stress (Chart 4, panel b).

Chart 4

Banks are exposed to CRE markets via loans with CRE purpose and with CRE collateral, but exposures are typically contained in size

a) CRE collateral on NFC lending | b) CRE exposures of euro area banks |

|---|---|

(percentage share of NFC lending) | (percentage share of total euro area bank assets) |

|  |

Sources: Panel a): ECB (AnaCredit) and ECB calculations. Panel b): ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: RRE stands for Residential Real Estate. Residential real estate owned by firms and financial institutions is included in the definition of CRE as laid out in Recommendation ESRB/2019/3. NFC stands for non-financial corporation. The date of observation is Q4 2023.

While banks remain the primary euro area lenders to CRE markets, non-bank lenders are also present. This is a sector where data gaps continue to pose challenges. Data shows that insurers lend to CRE markets, with a total outstanding loan book of €50 billion, of which €48 billion is directed to euro area companies (Chart 1). Market intelligence indicates that private credit lenders may also play a role in lending to CRE markets. In particular, they may provide credit to RECs facing funding gaps caused by falling asset values and tightening bank loan-to-value ratios (LTVs). A range of other non-bank entities may also provide credit to real estate markets, although their characteristics may vary across jurisdictions. For example, Moloney et al. (2023) document significant lending to Irish CRE market players by specialist non-bank property lending vehicles.

4 Bond financing of euro area commercial real estate

Bond markets, while small compared with direct loans, also represent an important source of funding for euro area real estate investors. Drawing on securities holdings data, it is possible to examine the holders of €490 billion in CRE-related debt instruments issued by euro area sectors.[12] At the end of 2023, outstanding debt securities issued by euro area RECs and REITs totalled €186 billion, of which ICPFs held €48 billion and other sectors – primarily investment funds other than REIFs – held €49 billion, with non-euro area investors holding €73bn (Chart 1). While covered bonds issued by euro area banks are typically linked to residential mortgage lending, banks have also issued around €266 billion in covered bonds linked to CRE lending.[13]

A significant shock to the CRE market could heighten the risk of default among RECs, leading to losses for holders of their bonds. This could prompt a wave of selling from investment vehicles like investment funds or ICPFs, exacerbating price declines and amplifying financial contagion risks (Chart 1). Where this results in rising financing costs for RECs, it may generate a further deterioration in the resilience of this sector, in turn driving further bond market stress.

Moreover, banks with large CRE exposures could face rising funding pressures via their CRE-backed covered bonds. Investors may liquidate positions in covered bonds, putting further pressure on bond prices and increasing funding costs for issuing banks. This could generate losses for investors in those bonds, which include euro area banks themselves as well as non-euro area holders (Chart 1), and may also affect banks’ wider real estate lending. While a number of euro area banks with particularly large CRE exposures have seen spreads on their covered bonds rise over the course of 2024, thus far we have not seen any contagion to wider covered bond markets.

Overall, holdings of CRE-related debt securities are not of a systemic size for any given sector, but they do add significant complexity to the financial system’s CRE exposures (Chart 1). CRE debt instruments, for instance, account for less than 1% of ICPFs’ total assets. However, their wide distribution also creates a complex map of interconnectedness, which could contribute to market uncertainty. Moreover, potential contagion effects and large losses among individual holders could still give rise to market stress.

5 Who is exposed via equity instruments?

At the end of 2023, listed and unlisted equity issued by RECs, REIFs and REITs totalled at least €1.4 trillion and was widely spread across sectors. We capture €488 billion in equity issued by RECs, which is predominantly held by euro area REIFs (€146 billion), non-euro area investors (€185 billion) and ICPFs (€92 billion) (Chart 1).[14] The outstanding value of shares issued by euro area REIFs is even larger (€913 billion), with an estimated €319 billion owned by ICPFs and another €90 billion in intra-sector crossholdings within the REIF sector (Chart 1). Non-euro area investors are also significant, owning €127 billion of REIF shares. The remaining €377 billion is distributed among domestic investors including banks, RECs, households and other financial institutions. Equity issued by euro area REITs amounted to €116 billion, with a substantial share held by non-euro area investors (€57 billion) and other euro area investors (€32 billion) – mainly investment funds and households (Chart 1).

Extensive equity financing across sectors represents a key channel through which a CRE shock could reverberate across the financial system. As noted in Section 2 above, RECs, REIFs and REITs have large exposures to physical CRE assets, which leaves them directly exposed to a downturn in CRE markets. Such a downturn could result in significant declines in CRE values and rental incomes, leading to portfolio losses, straining debt servicing capacity and possibly resulting in forced asset sales. Equity financing links between sectors are significantly larger in scale than bond financing. Consequently, rising losses among firms and funds would subsequently affect their equity investors, which would facilitate the transmission of losses across the financial system. This might create a link between losses among REIFs and ICPFs which have large exposures to REC, REIF and REIT shares.

Rising uncertainty or losses could also prompt equity investors to sell or redeem shares, potentially triggering negative feedback loops. This could further undermine the resilience of issuing funds and firms and further exacerbate CRE shocks. Any subsequent selling of shares or redemptions could spark additional feedback effects, such as forced property sales that have a further impact on CRE market values and result in diminishing equity valuations for issuers. Moreover, while equity financing is not associated with leverage, a decline in equity valuations could also result in RECs, REIFs or REITs breaching loan covenants or struggling to raise new equity, which would heighten the risk of forced deleveraging and procyclical sales of CRE.

6 Conclusions and way forward

Overall, this study demonstrates three key findings that are crucial for assessing how CRE shocks could propagate across the broader CRE market and impact financial stability. First, there are several sectors with particularly large exposures to CRE – especially physical CRE – both in absolute terms and relative to their total assets, which leaves them particularly exposed to CRE market downturns. This is particularly the case for RECs, REIFs and REITs (Chart 5). Second, structural vulnerabilities among these key CRE players increase their vulnerability to CRE market shocks and the likelihood that they could amplify these shocks. Among REIFs this vulnerability primarily arises from liquidity mismatch, while for RECs and REITs it arises from leverage. Third, the complexity of CRE exposures that arise from extensive debt and equity linkages between these key owners of CRE and their financiers adds a further layer of risk, as it could aggravate uncertainty and feedback loops. Some sectors are exposed to CRE markets via several channels, including direct holdings and a variety of financing mechanisms (Chart 5). Notably, losses for, and forced sales by, RECs, REITs and REIFs would not only have a negative impact on their own financial positions, but also lead to losses for interconnected financial institutions and destabilise the broader CRE market.

Chart 5

Domestic and foreign investors have substantial exposures to CRE assets

(left-hand scale: EUR billions; right-hand scale: percentage shares of total assets)

Sources: ECB (IVF, SHSS, AnaCredit), EIOPA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Moody’s Analytics, S&P Capital IQ, RCA, C&W and MSCI.

Notes: The date of observation is Q4 2023. “Other EA and non-EA” denotes other euro area and non-euro area investors. Physical CRE assets for these investors are based on a residual on the estimated total size of the physical euro area CRE market minus holdings by other domestic investor sectors. Due to data gaps, it is not possible to estimate the ratio of total CRE assets to total assets for this group.

Work on expanding and operationalising the use of macroprudential policies targeting CRE exposures should continue. The complexity of CRE markets is also a key reason why macroprudential policies for CRE are less advanced than those aimed at residential real estate (RRE). While euro area banks’ CRE portfolios are likely not large enough to threaten the sectors solvency, CRE-focused macroprudential tools could play a role in increasing resilience among more exposed institutions or in more exposed countries. Despite the known risks associated with CRE exposures, few euro area countries currently use macroprudential policy to target these risks. Behn et al. (2024) lay out how sectoral buffers could be applied to banks’ CRE exposures, although such measures will not affect non-bank financing of CRE activity. Similarly, while borrower-based measures have been an effective tool for targeting risks in RRE markets, the numerous financing sources available to CRE market players also create the scope for regulatory arbitrage via non-bank financing. At the same time, the complexity of financing may pose challenges for instrument calibration.

Furthermore, the potential risks posed by open-ended real estate funds to the broader financial system underscore the need to develop comprehensive macroprudential policies for the sector. It is crucial to develop a comprehensive macroprudential framework for such funds to address liquidity vulnerabilities. Among other things, this entails introducing sufficiently long notice periods – of at least 12 months, as proposed by the ESRB – for investors who wish to redeem their shares.[15] Moreover, given REIFs can also have large cross-border CRE exposures, the consistent application of such notice periods across euro area countries is essential to avoid potential arbitrage. Such a policy approach would bolster the resilience of euro area REIFs to CRE shocks and mitigate the potential for procyclical behaviours that could have an adverse impact on counterpart sectors and further destabilise the CRE market. Ultimately, this would enhance system-wide financial resilience.

The multifaceted nature of connections between actors in the euro area CRE market necessitates close monitoring and analysis. Policymakers and financial institutions must remain vigilant to evolving risks in CRE markets, as the complex nature of these financial linkages may exacerbate stress and propagate shocks across the financial system. Closing data gaps is a key element of this work. While this article has taken steps to cast new light on the links between the financial system and CRE markets, further data gaps remain. For example, it is crucial that work regarding the production of CRE price indices for all euro area countries continues and that reliable metrics of market health – such as vacancy rates – also become available. Similarly, it is essential to improve the data on non-bank exposures to CRE, including property characteristics and location, as well as on non-banks engaged in lending to CRE investors.

References

Behn, M. et al. (2024), “The sectoral systemic risk buffer: general issues and application to residential real estate-related risks”, Occasional Paper Series, No 352, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, June.

Daly, P., Dekker, L., O’Sullivan, S., Ryan, E. and Wedow, M. (2023), “The growing role of investment funds in euro area real estate markets: risks and policy considerations”, Macroprudential Bulletin, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, April.

European Central Bank (2024), Financial Stability Review, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, May.

European Systemic Risk Board (2024), ESRB response to the ESMA consultation on draft Regulatory Technical Standards and Guidelines on liquidity management tools.

Horan, A., Jarmulska, B. and Ryan, E. (2023), “Asset prices, collateral and bank lending: the case of Covid-19 and real estate”, Working Paper Series, No 2823, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, June.

Lang, J.H., Behn, M., Jarmulska, B. and Lo Duca, M. (2022), “Real estate markets, financial stability and macroprudential policy”, Macroprudential Bulletin, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, October.

Moloney, K., O’Gorman, P., O’Sullivan, M. and Reddan, P. (2023), “Non-bank lenders to SMEs as a source of financial stability risk – a balance sheet assessment”, Financial Stability Notes, Vol. 2023, No 11, Central Bank of Ireland, Dublin, December.

Ryan, E., Horan, A. and Jarmulska, B. (2022), “Commercial real estate and financial stability – new insights from the euro area credit register”, Macroprudential Bulletin, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, October.

Ryan, E., Jarmulska, B., De Nora, G., Fontana, A., Horan, A., Lang, J.H., Lo Duca, M., Moldovan, C. and Rusnák, M. (2023), “Real estate markets in an environment of high financing costs”, Financial Stability Review, Special Feature C, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, November.

Special thanks to Ana Maria Ceh for her contributions to this article, including data expertise, extensive risk and policy advice and feedback on earlier drafts. Many thanks also to Davide Samuele Luzzati for his valuable guidance and feedback.

A shock or downturn in CRE markets may include falling rents or property values, as well as broader declines in investor sentiment and increases in vacancy rates.

Note that this is a lower bound estimate of the total size of the physical euro area CRE sector, based on data for euro area countries from a number of commercial real estate data providers: Real Capital Analytics (RCA), Cushman & Wakefield (C&W) and Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI).

In aggregate, 80% of euro area REIFs have an open-ended structure, though there is substantial variation in this composition across countries (Chart 2, panel b).

It is important to note that the liquidity characteristics of open-ended REIFs in some countries may also mitigate potential liquidity risk, for example lock-up periods, infrequent dealing and notice periods. However, IVF data do not provide information on these characteristics. For example, the French Financial Markets Authority estimates that REIFs that are legally open-ended but operate in practice as closed-ended funds accounted for around 71 % of the total net assets managed by French REIFs in 2023. See Cartographie des marchés et des risques 2024.

This relates to a sample of 37 large REIFs, which represent less than 1% of the total REIF population of 7,488 funds as of the fourth quarter of 2023.

Real estate assets held by firms are approximated on the basis of their total long-term assets. To avoid double counting, the assets of subsidiaries whose parent is also included in the sample are removed. However, the complexity of corporate and financing structures used in CRE markets means that this cleaning step may not account for all interlinkages between firms.

It is difficult to provide a concrete estimate of the holdings of private firms, as most available data sources are unlikely to capture the entire universe of firms.

To find out more about this dataset, visit the AnaCredit homepage.

RECs include both landlords and developers, identified on the basis of their NACE code. REIF loan exposures are taken from the ECB’s Investment Funds Balance Sheet Statistics dataset (IVF). REITs are identified using categorisations from Bloomberg and S&P Capital IQ. These figures include loans to each of these counterparty types and loans to any entity which identifies one of these counterparty types as their immediate or ultimate parent. Total values for RECs assets should not be compared with total values for RECs bank loans, as the bank loan sample provided by AnaCredit is likely more complete than the asset sample provided by S&P Capital IQ.

Residential real estate assets owned by firms, which are also categorised as CRE under the ESRB (2019) definition, account for approximately a third of this figure.

For more information, visit the securities holdings statistics section of the ECB’s website.

This is based on estimates published by Moody’s.

Crucially, though, this may not capture specific shares issued by unlisted RECs that are held by private investors and high net worth individuals, for which data on holdings are not available.